|

THE MAKING OF A FRONTIER FIVE YEARS' EXPERIENCES AND ADVENTURES IN GILGIT, HUNZA NAGAR, CHITRAL, AND THE EASTERN HINDU-KUSH

BY

COLONEL ALGERNON DURAND, C.B., C.I.E.

THOMAS NELSON & SONS |

A. DURAND, The Making of a Frontier (1899)

|

THE MAKING OF A FRONTIER FIVE YEARS' EXPERIENCES AND ADVENTURES IN GILGIT, HUNZA NAGAR, CHITRAL, AND THE EASTERN HINDU-KUSH

BY

COLONEL ALGERNON DURAND, C.B., C.I.E.

THOMAS NELSON & SONS |

DEDICATED

TO

THE OFFICERS AND MEN

BRITISH AND NATIVE

WHO SERVED AT GILGIT

1889-1893

SOME word of explanation seems due when an unknown writer obtrudes a personal narrative on the public. My reason for writing this book was, that as the story of the development of the Gilgit Frontier, told in my letters and diaries, was read with interest by some who saw those papers, it seemed probable that its publication might give to those who have no chance of seeing the sort of life their countrymen lead on an uncivilised frontier, a faithful idea of what such an existence means. The book is a plain and unvarnished tale of the experiences of a frontier officer in times of peace as well as in those of war.

It was written under adverse circumstances, in the scanty hours of leisure snatched from official work in India, and it could not, for obvious reasons, have been published while I was Military Secretary to the Viceroy of India. The events it describes |8 began ten years and ended five years ago. It contains no information which has not been at the disposal of the man in the street, but it has this advantage: that, having been behind the scenes, it has been possible for me to avoid including the inaccuracies of the mere looker-on.

The book contains no dissertations on Frontier policy, no criticisms or attacks on those who direct that of the Government of India. I have no wish to join the bands who ride out to do battle with the windmills of the forward or backward policy, and it is, in my old-fashioned opinion, disloyal for an officer still in the service to criticise his superiors, even should he consider that he has grounds for his views, which is not my case. Moreover, such criticism is generally foolish; for the man on the Frontier sees but his own square on the chess-board, and can know but little of the whole game in which he is a pawn. It has been my aim merely to give a faithful account of the policy pursued on the Gilgit Frontier, of the steps taken to give it effect, and of the result attained. The reader who expects to find cut-and-dried dogmatic opinions as to the management of our relations with Frontier tribes will be disappointed. These, as a rule, can only be given, with their full effect, by men who know nothing about the question. |9

The reader also who expects to find a book on the Frontier stuffed with "tales of wild adventure ----mostly lies"----will not find them here. A certain amount of exciting incident there could not help being in five years' work in a wild country, but much of the book is a record of peaceful service. It tells of a constant struggle to raise a stretch of Frontier 300 miles in length from a condition of incessant war, anarchy, and oppression into a state of fairly established peace, prosperity, and good government.

For much of the ethnological information in the book I am indebted to The Tribes of the Hindu-Kush by Colonel Biddulph, who was for some time in Gilgit.

Owing to the courtesy of the Editors of the Fortnightly and Contemporary, I have been enabled to make use of articles published in their reviews, portions of which are incorporated in the book.

ALGERNON DURAND.

1900.

I. A MISSION OF ENQUIRY . . . . 15

II. FIRST VISIT TO CHITRAL . . . . 69

III. A MONTH IN CHITRAL . . . . 107

IV. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE GILGIT AGENCY ..... 160

V. VISIT TO HUNZA NAGAR . . . 199

VI. SECOND VISIT TO CHITRAL. . . . 234

VII. DARDISTAN ..... 264

VIII. FOLK-LORE AND SPORT . . . . 278

IX. ADMINISTRATION AND WAR . . . 300

X. THE HUNZA-NAGAR EXPEDITION. . 335

XI. THE INDUS VALLEY RISING . . . 356

COLONEL DURAND, C.B., C.I.E. Frontispiece

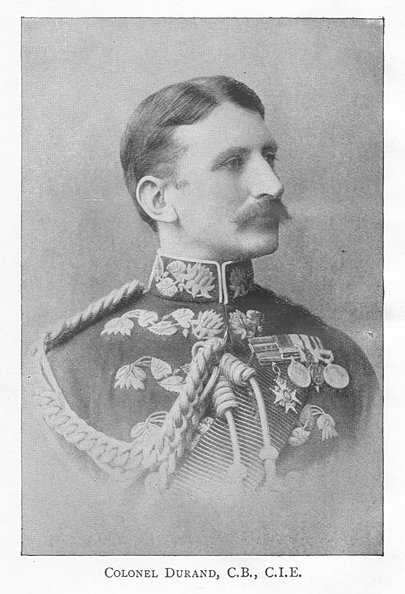

CROSSING A ROPE BRIDGE . . .112

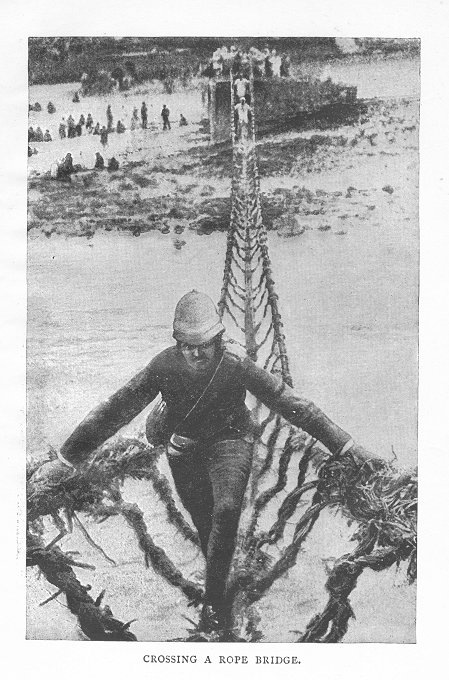

CHITRAL FORT AND VALLEY . . .160

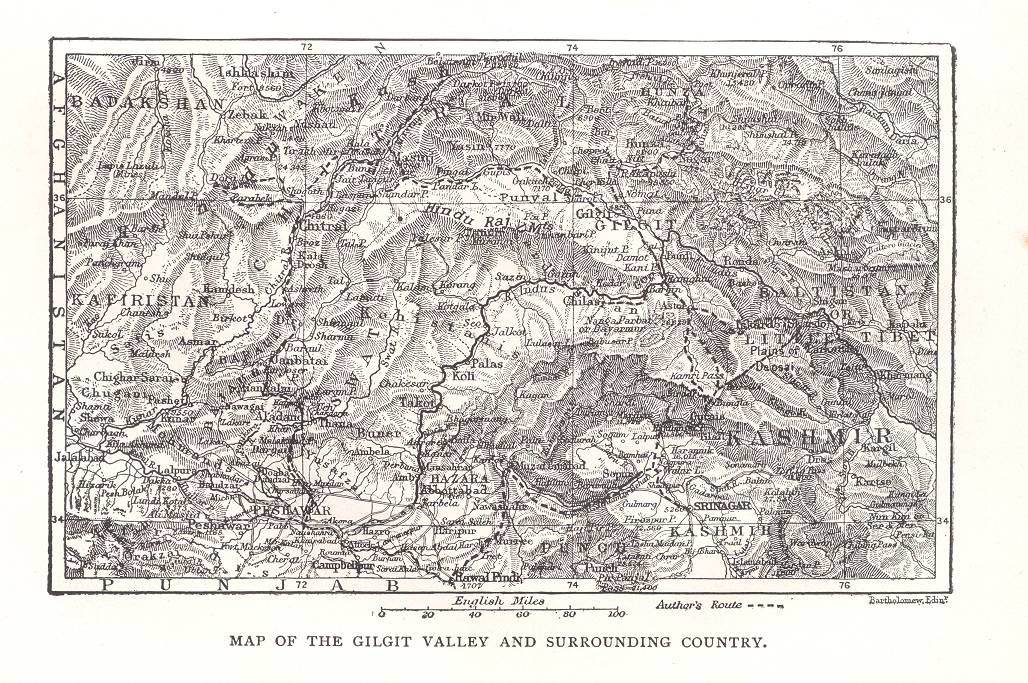

MAP OF THE GILGIT VALLEY AND SURROUNDING COUNTRY . . .192

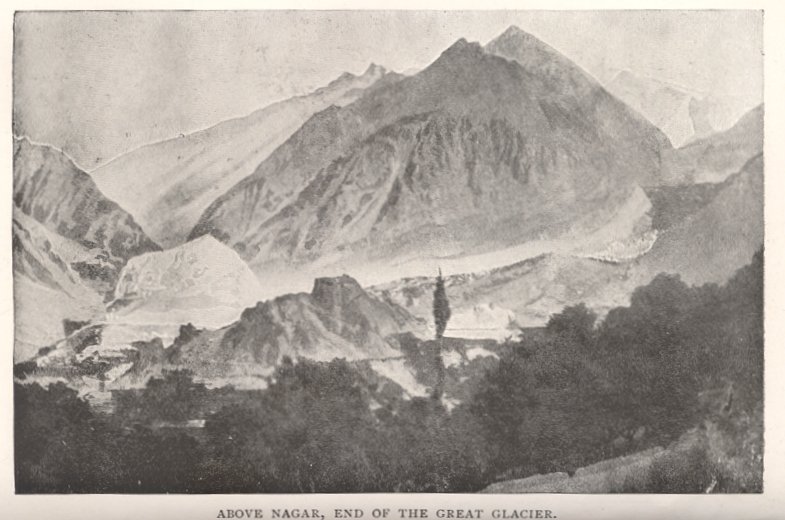

ABOVE NAGAR, END OF THE GREAT GLACIER ..... 256

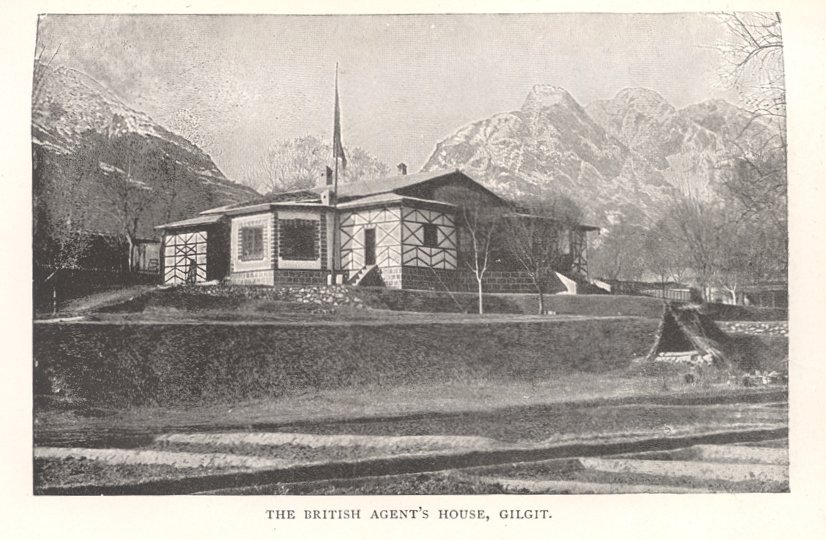

THE BRITISH AGENT'S HOUSE, GILGIT 288

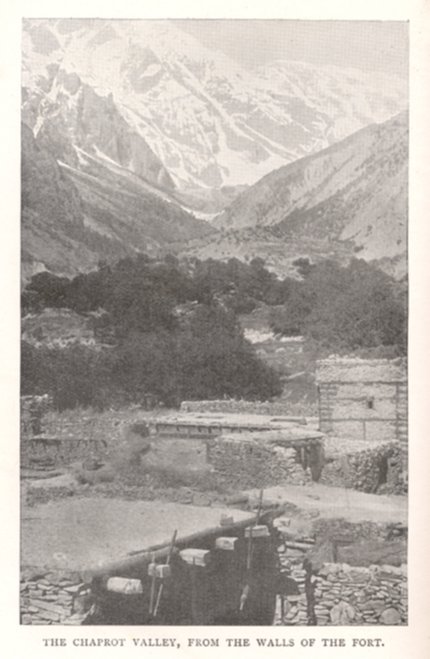

THE CHAPROT VALLEY, FROM THE WALLS OF THE FORT . . . 320

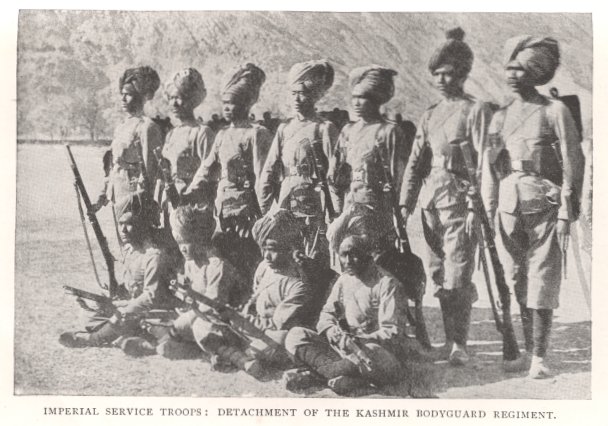

IMPERIAL SERVICE TROOPS: DETACHMENT OF THE KASHMIR BODYGUARD REGIMENT . . . 352

[These face the pages above in the printed text -- in the online text, I have placed them near the same places.]

A MISSION OF ENQUIRY

THE interest which attaches to the work of Englishmen on the borderlands of our great Empire has prompted me to write the following plain record of work and travel in the Hindu-Kush. For four years Warden of the Marches on the northernmost point of our Indian frontier, it was my good fortune, in peace and war, to deal with the most primitive races, to penetrate mountain fastnesses where the foot of a European had never trod, and to wander through the most magnificent scenery that the eye of man has ever looked upon. I trust, therefore, that the following pages may give some idea of what life on the frontier really means.

The stretch of frontier to which I refer lies south of that portion of the Himalayan range which divides |16 Chinese and Russian Turkestan and Eastern Afghanistan from the Indian Empire. Officially it is known as the region of the Eastern Hindu-Kush. From east to west its length is some five hundred miles; from north to south its depth is about a hundred and fifty. It comprises the districts and States of Baltistan or Little Thibet, Gilgit, Hunza and Nagar, Chitral, and the Indus Valley from Bunji to Sazin.

The whole of these are either directly under the rule of, or tributary to, Kashmir, which State again is one of the most important of the Native States of India acknowledging the suzerainty of the Queen.

The importance of this portion of the frontier lies mainly in the proximity of the Russian outposts.

It is difficult of access. Gilgit, which is roughly its centre, lies four hundred miles from the line of railway at Rawal Pindi in the Punjab, and the only road leading to it, over which we have permanent control, runs over high passes closed for six months of the year by snow. From a military point of view, therefore, it is a bad position in which to lock up troops. But military considerations alone cannot decide the actions of a Government.

The Sikhs, during the time they ruled Kashmir, had been drawn into crossing the Indus at Bunji, |17 owing to the persistent aggression of their Gilgit neighbours. The Dogras, the present rulers of Kashmir, had inherited their responsibilities, and had added to them by contracting agreements with the neighbouring States. As the suzerain power the responsibilities of Kashmir became ours, and it was recognised that the Hindu-Kush for these hundreds of miles must be our natural frontier.

If I have mentioned Russia, it is not to enter into dissertations as to the feasibility of her attacking India. The Great Empire----the coming shadow of which Napoleon saw with prophetic eye----is expanding in many directions. Central Asia is now hers. That her soldiers, and the ablest of them, consequently believe in the possibility of conquering India, no one who has had the chance of studying the question can doubt. Her diplomats may not consider the task one to be undertaken----they are fairly busy elsewhere. None the less do her tentacles creep cautiously forward towards our Indian frontier. To-day it is the Pamirs, to-morrow it will be Chinese Turkestan or part of Persia, which is quietly swallowed. For every point of possible attack gained is to her advantage, and every man of ours who can be kept locked up in India, or guarding its frontier, when the Battle of Armageddon does come, must be |18 withdrawn from the real chessboard, wherever that may be. That, to my mind, is the crucial point.

If this is no place to discuss "the Russian menace," still less is it to raise the vexed question of frontier policy. I am no believer in catch-words, though they are useful as terms of abuse. The "forward policy," and that of "masterly inactivity," have been wrangled over quite sufficiently. No sensible man nails either colour to his mast. Circumstances, and the races you have to do with, decide cases. Successive Cabinets in England, Conservative and Radical, agreed with the Government of India, that in the case of the Gilgit frontier certain steps were necessary, and the steps were taken. The following pages tell the tale of what was done.

In the summer of 1888 an officer of the Quarter-Master-GeneraPs Department being required by Lord Dufferin's Government to visit Gilgit to enquire on the spot into the causes which had led to the outbreak of hostilities between Kashmir and two of its tributary States, Hunza and Nagar, I was fortunate enough to be selected for the duty.

Once or twice before the name of Gilgit had appeared for a moment, to be forgotten again immediately. The adventurous traveller, Hayward, had been murdered in the neighbouring valley of Yasin |19 under circumstances of the blackest treachery, and his bones had been laid to rest in Gilgit. An English officer, Major Biddulph, had, in Lord Lytton's Vice-royalty, spent some years there, and had been recalled from the too isolated position after a stormy experience. A mission under Colonel Lockhart, now Sir William Lockhart, Commander-in-Chief in India, had wintered at Gilgit, and from it, as a base, had traversed Hunza, crossed the Hindu-Kush, passed through Wakhan down the Ab-i-Panja, the southernmost branch of the Oxus, and had traversed Chitral territory from end to end. A few adventurous travellers and sportsmen had visited Gilgit, but to most men in India it was a name and nothing more. My satisfaction, therefore, at the thought of penetrating to this little known country was great.

My brother was at the time Foreign Secretary to the Government of India, and from him at Simla I received all the information available on the subject, and my instructions. These preliminaries completed, I started for Gilgit.

At Rawal Pindi, the railway terminus for Kashmir, I found my companion, George Robertson, now Sir George Robertson, K.C.S.I., it having been decided that a doctor should form one of the little party of two. Nothing can, it is said, be such a test |20 of compatibility of temper as travelling with only one companion for a length of time. For four months we lived alone together, sharing the pleasures and troubles of hard travelling, and we emerged from the trial the fastest friends. With such a companion, delighting in the people, the scenery, and the novelty of the life, the four months of marching was a continual pleasure.

From Rawal Pindi, where the rail is left, the road into Kashmir runs for forty miles uphill to Murree, the summer headquarters of the Punjab Military Command, and from there descends twenty-eight miles to Kohala, in the valley of the Jhelum, which river is here the boundary between British India and Kashmir. The Jhelum is crossed by a suspension bridge at Kohala, and from this point the road runs for over ninety miles along the left bank of the river till it debouches at Baramulla into the main valley of Kashmir, within a few miles of the spot where the river leaves the Woollar Lake. The road is a very fine one, admirably aligned, but at the time I write of it was only partially completed, and we had to march about half the distance between Kohala and Baramulla, at which place the traveller into Kashmir usually enters the boats that convey him to Srinagar, the capital of the Kashmir State. |21

In the summer the heat in the Jhelum valley is very great, and though the scenery is fine, the river in a constantly recurring series of rapids cutting its way through the gorges of the impeding hills, there is not anything as a rule of remarkable beauty, and one's only object is to get through the journey as quickly as possible. The last few marches, however, are striking. The road runs below great cliffs clothed with forest, at one time through the terraced fields of rich rice cultivation, at another through thickets of lilac, barberry, and hazel, and at another through the forest itself, here composed of magnificent deodars. Ruins of Buddhist temples by the roadside----some of them of great interest, and in a fair state of preservation----bear witness here, as do other remains on every well-known natural line of communication throughout the Hindu-Kush and Northern India, to the widespread power of the creed once ruling from Kandahar and Kabul to Bengal, of which now throughout the continent of India, scarcely a trace remains, except in time-worn stones.

The valley of Kashmir, which is about eighty miles long by twenty broad, contains and leads to some of the most beautiful scenery in the world. Shut in by a great circle of snowy mountains, |22 traversed by a fine river running through richly cultivated lands, adorned by a chain of lovely lakes, watered by a thousand streams, covered with numerous villages embowered in every species of fruit-tree, with lake and stream bordered by plane-trees, the magnificent "chenar," dear to the Mogul Emperors, and planted by them wherever they loved to dwell, the vale of Kashmir is, outwardly at least, the earthly paradise of the East.

The traveller generally leaves Baramulla in the evening, and his barge is paddled and towed up by sunset to a spot where boats tie up for the night. From this point, at early dawn, a start is made to cross the Woollar Lake. This great stretch of water has an evil name among the boatmen, for it is subject to swift and terrible storms, against which the keel-less boats, with their heavy top hamper of mat roofs, cannot possibly make head. It is an unpleasant experience to be caught in a storm on the lake. All that is feasible in this case is to drift with the wind, paddling as rapidly as possible towards the nearest reed bed, and to tie up there till the storm is past; but many a boat caught in the open lake has been swamped, and the boatmen are full of tales of shipwreck. By starting before sunrise it is possible, however, to cross by mid-day to the other side of the lake, |23 where the river flows into it, and storms as a rule do not come down till after-noon.

The scene as your boat steals out into the lake an hour or more before sunrise is one never to be forgotten; many a time did I get up to enjoy it, and each time new beauties revealed themselves. It always reminded me of a picture of the Dutch School in varying gradations of pearly greys. The night has passed, and the cold, clear light of dawn steals over every feature of the scenery. The great snow mountains stand out white and pure against the cloudless sky, in which the morning star still burns; not a touch of pink has yet warmed their silent summits. Reed beds, swathed in gently-moving mist, and long grassy promontories, on which stand motionless cattle, project into the lake in ever-varying outline as the boat glides on, all showing grey in the yet sunless light. The weird call of the water-pheasant sounds on all sides, as the black and white birds, disturbed by the sound of the paddles, wheel over the marshes; and for miles around you stretches the great expanse of water, cool and grey, swept here and there with washes of pale blue, or dark-blue greys where the lake shallows.

The journey up the river, though it offers many beautiful views, is monotonous, and it is a relief to |24 get out of your boat occasionally, and to walk along the bank ahead of the men towing, or to cut off bends of the river by striking across country. In the spring the banks of the Jhelum are bordered for miles by broad bands of purple iris, with an occasional mass of the white iris showing the village graveyard; the air is delightful, and breathes new life into any one who has come up from the burning plains of India. When tired of walking there is nearly always a clump of the great plane-trees, or a single one growing on the river bank, to give the wayfarer pleasant shade, where he can sit and wait for his boat, sung into day-dreams of home in the far West by a chorus of sky-larks.

Srinagar itself is picturesque as approached by boat. The town, a huddled mass of lightly-built houses, in the construction of which timber takes a prominent part, lines both banks of the river. It is dominated by two isolated hills, one crowned with the battlements of the State prison and fortress called Hari Parbet, the other the Takht-i-Suleiman,or Throne of Solomon, topped by an ancient temple which has looked down on the crowded life below for many centuries, for it was built before the secret of the true arch was known. Behind these hills rise the rugged outlines of the mountains which form the boundary |25 of the valley. As your boat ascends the stream it passes under bridge after bridge of wood built out from massive wooden piers on timber cantilevers, and the bank is lined with temples, whose roofs, covered with tin, shine like silver. Ruined quays, retaining walls of masonry, in which can be traced the spoils of many a temple; ill-kept flights of stairs leading to filthy gullies, or here and there to broader roads; houses leaning at all angles, telling of the passing of the last earthquake; one wooden Mahomedan mosque, with a roof recalling Chinese architecture; the great mass of the Maharaja's palace, broken by the golden dome of the princely temple----all these combine to make a picture unique in the East. Passing under the last bridge your boat floats into a long reach, bordered on the left with stately planes and long lines of poplars, amongst which you land at the gate leading to the Residency, where lives the officer belonging to the Political Department of the Government of India, who holds the post of Resident in Kashmir. The house is a charming one, the most English house in India, but it is very badly situated, and lies below the bank of the river scarcely above the ordinary high-water level, and it has more than once been in imminent danger of being flooded out. A few words as to the position of a Resident in a |26 Native State may not be amiss. There are in India, surrounded by districts entirely under British rule, or lying, as in the case with Kashmir, on the borders of the Empire, some hundreds of Native States, great and small, having a total population of over eighty millions. These States, for want of a better word, may be described as feudatories of the Suzerain Power. Their relations with the latter pass through a thousand gradations, from quasi-independence to complete subservience. Hundreds of treaties, engagements, and grants ratified during the past hundred and fifty years, define their position and the duties of the contracting powers. In no case has a Native State the power of waging war, and no external relations can be entered into. The powers of the ruling chiefs, the forms of internal administration, vary in innumerable ways; at one end of the scale you may find the constitutional government of a State like Mysore, with its elaborate systems of revenue and education, its assemblies and councils; at the other the rude patriarchal rule of a border chief; but in all cases in the background, ready to further schemes of improvement, or to step in should mismanagement lead to oppression and danger, stands the, paramount power of the British Crown. The greater Native States have all a resident political |27 agent living in the State, the smaller, as a rule, have a political officer in charge of a collection of three or four of them. The whole of the work in connection with Native States which needs to be referred to the Government of India passes up to the Secretary in the Foreign Department, under whose orders, with exceptions which do not affect the general question, are the officers employed in the most important of the Native States. The head of this great department works directly under the Viceroy.

The department is recruited at the bottom from the ranks of the Indian Civil Service, and from officers of the Indian Army. Promotion in the higher grades is not necessarily by seniority, Government reserving itself the right to bring in suitable officers from other departments whenever advisable. Many of the highest offices are often thus filled, distinguished officers of the civil or military service being brought in at the top of the tree.

Mr Chichele-Plowden, then Resident in Kashmir, very kindly put us up in Srinagar. The first thing to be done was to pay my respects to the Maharaja, which I did in company with the Resident. My reception was exceedingly warm and cordial; an old-established friendship of many years' standing had existed between the Maharaja's father and mine, and |28 this was extended at once to the next generation. I found the Maharaja's brothers, Raja Ram Singh, the Commander-in-Chief of the Kashmir State, and Raja Amar Singh, who shortly after became Prime Minister and President of the State Council, equally disposed to be friendly. The acquaintance so auspiciously begun, ripened, I am glad to think, into warm regard and friendship, and during the five years I was connected with the affairs of Kashmir I received, however inconvenient my demands may have sometimes been, the heartiest assistance.

I found the Maharaja quite satisfied with the idea of my going to Gilgit, and, if necessary, on to Chitral, but he was very averse to my going to Chaprot. This was the frontier fort out of which the Kashmir garrison had been turned by the Hunza-Nagar combination during the preceding winter, and the Maharaja had not yet heard of its having been re-occupied by his forces. He was very averse, therefore, to my adventuring myself north of Gilgit, and as I, on my part, had not the least anxiety to have my throat cut, or to fall a prisoner into the hands of the tribesmen and to bring difficulties on Government, it was agreed that my movements, after my arrival at Gilgit, should depend on the position of the Maharaja's |29 troops and the advice of His Highness's local authorities.

The occupation of the Gilgit district had never paid. The Dogras had suffered heavy loss in it again and again, but the honour of the Kashmir Durbar (the title usually applied to the government of a native state), would not for a moment permit of withdrawal. Moreover, withdrawal would not have answered the purpose of securing peace; it would merely have opened, by uncovering the right bank of the Indus, a road constantly used in former days for raiding into Baltistan or Little Thibet, the next province on the north-east belonging to Kashmir. The remedy would have been worse than the disease; a State which begins retiring is in the East the natural and lawful prey of its adventurous neighbours. I found no question of withdrawal being discussed; the attention of the Durbar was entirely turned to securing its position on the frontier, and to retaking the Fort of Chaprot. Throughout the winter nothing could be done, the passes leading to Gilgit were closed by snow, but with the return of spring every nerve had been strained to accomplish this object.

The Durbar was immensely proud of its army, which at this time was very numerous and costly. |30 It was quite ignorant of the fact that the army was without the very rudiments of organisation, that it was merely an unwieldy agglomeration of units, and that its leaders, men for the most part of good family and of fighting instincts, were one and all as innocent as the babe unborn of the art of war. Trusting to the numbers of their troops and to the well-known gallantry of the Dogra race, the rulers in Kashmir seemed determined to restore order on the frontier, and to wipe out the disgrace which had been inflicted on their arms.

Ignoring the enormous natural difficulties of the country, the villainous state of the existing tracks ----roads there were practically none, when once the valley of Kashmir was left----and the conditions under which an expedition on its frontier must be carried on, the Durbar all through the spring and summer of 1888 poured thousands of men towards Gilgit. The army was without a trained general, had no staff, no proper transport, commissariat, medical, or ordnance departments, and was in short a mass of armed men without the semblance of organisation. The operations at Gilgit against the Hunza-Nagar tribesmen were to be directed by a committee of generals and sirdars, assisted by the Governor of Gilgit. Such an arrangement would elsewhere have |31 been recognised as ensuring the failure of any military operations. As a matter of fact there was in the end no fighting, which was a mercy, considering the condition of the Kashmir army. The Durbar built a golden bridge for its revolted vassals, peace on the frontier was temporarily patched up, and the Kashmir troops, with the exception of the usual garrison, were withdrawn from Gilgit by the autumn. After paying a farewell visit to the Maharaja, we started in one of His Highness's house-boats for Ban-dipur, the place on the Woollar Lake from which the road to Gilgit starts. The distance between Bandi-pur and Gilgit is about a hundred and ninety miles.

At Bandipur we were met by two officials of the Kashmir State, who had been deputed to accompany me----the one with strict injunctions never to lose sight of me for a moment wherever I might go, the other with orders to see me as far as Gilgit. A guard of twenty Kashmir sepoys, Dogras of one of the best regiments, had also been told off as my escort. I had, in addition, four Pathan orderlies belonging to my regiment, the Central India Horse. They were picked men of tried gallantry, true as steel, worthy of the implicit trust I placed in them. The baggage of the party was carried by coolies, the roads not being suitable for animal transport. |32

The second of the Kashmir officers was a charming companion, a Hindoo gentleman of the old school, who had passed much of his life at the Kashmir Court. Bright, always cheerful, with a supreme contempt for the savage people among whom we were to spend our time, and also it must be allowed for the beauties of their wild country, he invariably saw the amusing side of life, and was ready to extract some fun out of the difficulties and mishaps of frontier travel. We became the greatest friends, and spent hours in endless talk. The last time I saw him his humour was a trifle gruesome. He came to take leave of me, and told me with much glee how the Brahmin astrologer whom he had consulted about his return to Kashmir had fixed the lucky day for his start, but had not been able to foresee his own departure on a longer journey. The unfortunate man had died of cholera that morning.

From Bandipur the road runs straight out of the valley over the Tragbal pass, the highest point of which is about twelve thousand feet. Our first camp was at an altitude of over nine thousand feet in a glade in the pine forest, the turf covered with blue forget-me-nots. The march up was lovely, through one succession of copses of jasmine and scented wild rose, the latter of all colours from white to dark red. |33 Close to the camp we came on the first signs of the army which had preceded us----a line of graves of men who had died of cholera. The troops and coolies were said to have suffered much from this scourge, and we arranged to avoid their camping grounds in future. The following morning we continued our march, the road winding up through pine forest till the rounded tops of the watershed were reached. We halted for an hour at the top, surrounded by a wilderness of flowers, blue gentian, anemones, acres of white and yellow blossoms bordering the wreaths of snow, masses of small pink alpine flowers, wild rhubarb and sorrel in profusion, and patches of dwarf juniper, for we were well above the pine and birches. The views from here are lovely----to the left, steep pine-clad slopes descend into the famed Lolab valley, behind, stretched out thousands of feet below, lie the valley of Kashmir and the blue sheet of the Woollar Lake, backed by the snowy range of the Pir Panjal; to the right stand the great square peak and snowfields of Haramukh; in front, a hundred miles away, towers Nanga Parbat, from which on both hands as far as the eye can reach tossed ranges patched with snow fill up the picture.

I had an example on reaching camp this day of the extraordinary carrying power of the Kashmiri |34 coolie; my tent was late coming up, and when it arrived I found one man carrying it, a large solid leather kit bag, and his own rations. The weight was at the least a hundred and fifty pounds. I was extremely angry, and made it very unpleasant all round, as plenty of coolies had been arranged for. Nothing of the sort ever occurred again, but my orderlies told me, and I saw enough to show that the report was true, that the sepoys treated the coolies like dogs, and beat them as they would a beast of burden. The fact is, the Kashmiri villager proper, to which class our carriers belonged, comes of a race that has been mercilessly oppressed for centuries by foreign Mahomedan rulers from India. Being a Mahomedan, he has been specially ill-used since Kashmir passed under Hindu rule. The sepoys and officials of all classes are almost to a man Dogras and other Hindus who have absolutely no sympathy with the Kashmiri. The race is physically fine, great, strong men and well fed, but morally they are, what their oppression has made them, liars and pitiful cowards, who cringe to the stick of the sepoy like spaniels. My coolies said they were never paid when employed on Government work, and that they generally had to supply their own rations. They certainly expected no pay on this occasion, and were delighted |35 and astonished beyond measure when I saw them paid myself. The Durbar made nothing by the transaction when coolies were impressed, it was duly charged for their hire, but the money stuck in the hands of those drawing it. A new era has now opened, owing to the revenue settlement carried out by my friend, Mr. Walter Lawrence, a distinguished member of the Indian Civil Service, whose services were lent to the Durbar for this purpose by Government. The villagers are no longer liable to be dragged out for forced labour if they do not satisfy the extortionate demands of tax collectors and plundering officials. But it will take many a long year before the Kashmiri becomes a man.

The next few marches are up the valley of the Kishengunga, one of the most beautiful in Kashmir. The road runs for the most part near the river, through fir forest and thickets of deciduous trees and bushes, amongst which the white Persian lilac and wild roses show in great profusion. At the lower end of the valley is a splendid grove of branching poplars, beyond which, near Gurais, are a few miles of open cultivation and stretches of meadow land. The steep hill sides for the most part, however, close in on the river; the slopes facing north covered with forest, those facing south bare of trees but grass grown, as is |36 usual in the Himalayas, where the summer sun burns up the southern exposed slopes too much to permit of young woods growing. The mountains rise in grand peaks, broken into precipices hung with fir and birch, and interspersed with alpine meadows.

The height of the Gurais valley is about eight thousand feet, and the climate as near perfection in spring, summer, and autumn as can be found on earth. We habitually marched early for the sake of the coolies, starting any time after four or five, stopping to breakfast at some tempting spot, where we would spend most of the day reading or wandering off the road in search of views and game, and finally reaching camp some time in the afternoon. It was the existence of the nomad, the charm of which once tasted works like madness in the blood, and suddenly fills the sufferer, when mewed up within the four walls of a house, with a wild longing to be away, wandering, it matters not where. I had my fill of it for five years, and nothing comes up to it for pure enjoyment.

The road out of the Gurais valley is either by the Kamri Pass or the Burzil. We chose the former, as by it the distance to Astor is about a march shorter. The road over the Kamri leaves the valley at the village of Bangla, goes straight up the side of the hill, |37 and crosses the ridge at an altitude of over thirteen thousand feet. The ascent is very severe, but on the other side the descent is gentle. We camped on both sides of the pass just below snow level in most delicious air, like Northumberland in clear autumn, and again our marches were through miles of flowers, acres of spirea, and thickets of roses in full bloom.

The road requires but little description. Across open downs or grassy slopes it was simply the footpath worn by men and animals. In narrow valleys it wound in and out, now at the level of the stream, again a hundred feet up, over boulders, stone staircases, and along shelves of rock, anywhere and everywhere, so long as man and beast could find a foothold. Perhaps a quarter of the length of the road may be said to have been made, the rest had evidently "growed."

As we dropped down towards Astor the valley we were in deepened, and was crowned by perpendicular cliffs broken into the most fantastic shapes. We began now to get occasional glimpses of Nanga Parbat, 26,620 feet high, which dominates this part of the country, and close under whose shadow we were marching,----magnificent views, giving an overpowering impression of towering height. Locally it is called Deomir, "the mountain of the gods," a fitting name. |38

The last few marches showed miles of terraced land out of cultivation, the result of the incursions of the murderous Chilasis who raided from the Indus valley. In a country where every foot of cultivation has to be won with heavy toil from nature, nothing appeals so to your heart as the sight of deserted land and ruined homesteads.

Finally, after thirteen days' marching, we reached Astor, which used to be the capital of a kingdom important enough in a small way in the Hindu-Kush. The Sikhs absorbed it, all that remains of its former glories being a fort now held by the Dogras.

Astor boasts of a bazaar, the first met with since leaving Kashmir; beyond it there are only two, at Gilgit and Chitral. Most of the trade was at this time done by itinerant traders from Koli and Palas in the Indus valley, who brought goods from India, taking back gold-dust and products of Central Asia, and who penetrated into the remotest glens. The more peaceful state of things which we introduced has given a start to Gilgit, which is now becoming the emporium of this portion of the Hindu-Kush.

I here made the acquaintance of Bahadur Khan, Raja of Astor, the representative of the old ruling race, an old gentleman whose honesty, intimate knowledge of the country, and connection with all the |39 local rajas were to be of the greatest value to me on more than one occasion. Deprived of his kingdom and very poor, living on a small grant of land given to him by the Durbar, treated with contempt by the Kashmiri Governor of Gilgit, under whom is the valley of Astor, he had the loyalty and respect of his former subjects, who reserved for their Kashmiri rulers the hatred, fear, and contempt begotten of oppression.

We saw at Astor for the first time polo as it is played in what is either the home of its birth or the land of its earliest adoption. In very few places does flat open ground exist; consequently the polo grounds are merely terraces annexed from the cultivation, through which, as a rule, the main road into the village runs. The Astor ground is about a hundred and fifty yards long by twenty yards wide, and it is one of the best. Any number of men play, the usual limit is ten-a-side, and at the beginning of the game both sides assemble at one of the goals. When all is ready the captain of one side, usually the local raja or the most important guest, dashes down the ground at full speed, carrying the ball and followed by the whole mob of players, all shouting madly; the band, which is seated outside the boundary wall at the centre of the ground, plays its loudest, the lookers-on |40 yell and whistle in a way a London street boy might be proud of, and, without checking his speed for a moment, the holder of the ball throws it into the air and hits it as it falls. The hit should be made from the centre of the ground, and a good man will often hit a goal. A man who is inclined to be a bit too sharp will gallop well beyond the centre before hitting, and gain an unfair advantage. One of my worst enemies, who murdered his brother because he was a friend of ours, who gave me endless trouble, and finally made war on us, but on whom the hand of Fate at last descended with crushing power, always cheated in this way. I used to think it was very typical of his brutal, overbearing, treacherous nature.

The game is very rough and ready, and each goal hit produces a wild mêlée, as the striker or his side must be able to pick up the ball for the goal to count. The man who has hit the goal will throw himself off his pony and try and pick up the ball, while the other side, with fine impartiality, hit him or the ball, or ride over him, in their endeavours to save the goal. Why each game does not end in sudden death and a general free fight I could never imagine, but a serious accident is rare. In most parts the losing side has to dance before the winners when the game is over. As all the men |41 love dancing, this is no great hardship. With the advent of the British Subaltern the polo rules of the Hindu-Kush have undergone revision and improvement.

A day at Astor enabled us to rest our camp and attend to letters. Then we started again, double marching ourselves to Doian, the last stage before the descent into the Indus valley is made, where I proposed to shoot for a few days in the Lechur, one of the nullahs leading into the Indus, and good for markhor. Our camp was to go on by single marches to Bunji, where the Indus is crossed.

The character of the mountains now began to change completely. Below eight thousand feet hardly a tree is to be seen, except where irrigation fertilises the lands of a village. Steep bare hillsides, streaked with reds and ochres, but generally grey and pale sandy yellow, covered where anything will grow with wormwood scrub, plunge down thousands of feet into the valleys, which are only wide enough at the bottom to admit the passage of the chafing stream. If you happen fortunately to be about the altitude of eight to twelve thousand feet, where the rain falls, you will march through forest and grass lands. Above that, again, run bare rock-strewn hillsides, the last vegetation being |42 always the dwarf juniper, and from thirteen to fourteen thousand feet is the line of eternal snow. As a rule your road runs in a valley as near the bottom as possible; for days at a time you see no forest; when you do see it, it is a green patch thousands of feet above you, and you only get an occasional peep at a snow peak. Mile after mile of arid sand and rock is passed, unrelieved by a single tree, except where a stream has cut its way from the higher hills and piled up an alluvial fan at right angles to the main valley. Then you find a lovely little oasis of green terraced fields running hundreds of feet up the hillside, a village embowered in fruit-trees and vines, and you sit down and thank God for the shade.

The march to Doian was severe; the road ran first through scattered forest of edible pine and pencil cedar, then dropped into the river-bed to climb, by laborious zigzags, a thousand feet to avoid a cliff. This was repeated again and again, the road running occasionally for miles in sand full of loose stones, the debris of the hills above. The last ten miles of the march is, however, lovely: much of it through one of the finest pine forests in the world, which fills an enormous bay in the hills. The moon had risen before we reached camp, and the view, as |43 we topped the last spur and saw below us the twinkle of the torches carried by the men coming to meet us, was one I shall never forget. A veil of mist, flooded by brilliant moonlight, stretched across the great abyss which yawned a thousand fathoms deep at our feet, and turned the peaks of the Hindu-Kush, which lay before us, into visionary delectable mountains of Beulah, barred with silvery grey.

Whatever dreams the beautiful scene evolved were rudely dispelled. We had only the inside fly of one tent, and were sleeping on the ground, having come as light as possible. It began to rain steadily directly we got to bed, and poured all night. I managed to keep perfectly dry, sleeping in an explorer's bag, but the unfortunate Robertson, with nothing but waterproof sheets, spent the night in pools of water. We stayed at Doian a few days, and I was lucky enough to get a fine markhor with a forty-seven-inch head.

We moved up to a camp about eleven thousand feet high, from which we had the most superb views. We were on a spur of Nanga Parbat, the watershed between the Indus and Astor river, and surrounded by a complete ring of snow-peaks, the average height of which is about twenty thousand feet. The view from the crest, a couple of thousand feet above our |44 camp, is one of the finest I should think in the world, certainly one of the finest in the Hindu-Kush. In a gorge nine thousand feet below, at your very feet, runs the Indus, giving that depth and proportion which is so often lacking in a mountain view; to the south, solitary, sublime, rises in one sweep from the spot on which you stand the mighty mass of Nanga Parbat, thirteen thousand feet of snow-field and glacier; to the east, magnificent peaks succeed each other till they join the main chain of the Hindu-Kush, which stretches in an unbroken line before you; while to the west the Hindu Raj towers over the Indus, backed by the snows of Chitral and of the Pathan Kohistan.

It is very rare to get a view which gives you a range in height of twenty-two thousand feet, but when you are fortunate enough to obtain it the effect is overpowering. The Hindu-Kush once seen in its most majestic aspects crushes all comparison.

We spent several days in this shooting camp, and then moved down again to Doian and started for Bunji, where the Indus is crossed. The march was the worst on the whole road. Running along the last spur between the Indus and the Astor river the path struck the watershed at the height of ten thousand feet, and then dropped down the Hattu |45 Pir six thousand feet in about five miles to Ramghat, or Shaitan Nara, the "devil's bridge," as it was more appropriately called, until the Maharaja piously renamed it. It is impossible to exaggerate the vileness of this portion of the road; it plunged down over a thousand feet of tumbled rock, in steps from six inches to two feet deep; then for a mile it ran ankle-deep in loose sand filled with sharp-edged stones; it crossed shingle slopes which gave at every step; it passed by a shelf six inches wide across the face of a precipice; in fact it concentrated into those five miles every horror which it would be possible to conceive of a road in the worst nightmare, The culminating point was that, for the whole way from top to bottom, there was not a drop of water to be found on it, not an atom of shade. With coolies in the hot weather the only way to tackle the ascent was by marching at night and sending on water half way for them; the descent we managed fairly comfortably by starting at from two to four in the morning. The road was so execrable that ponies which had made the trip once from Astor to Bunji were always considered unfit for further work without a fortnight's rest and good grazing. The Hattu Pir was a Golgotha; the, whole six thousand feet was strewn with the carcasses of expended baggage animals, and in |46 more than one place did we find a heap of human bones.

Ramghat was a place of the greatest importance, as the only line of communication between Gilgit, Astor, and Kashmir crossed the Astor river here. It is a weird spot; the river about a hundred to a hundred and fifty feet wide dashes through a gorge, making two turns at almost complete right angles, so that, standing on the bridge, you cannot see more than a couple of hundred yards in all. The force of the water is terrific, the noise deafening, and the heat in summer awful. The river was bridged by a rope bridge, and also by a wooden cantilever bridge of great length and doubtful strength, which rocked and swayed in a way to try bad nerves. This bridge had no hand-rail, was about five feet wide, and fifty feet above the water; it was not safe to ride over, though my engineer friend, Colonel Aylmer, V.C., when up with me, used habitually to ride over it and every other similar bridge in the country. But then his nerves were not those of the ordinary mortal. Once, when leading my horse over it, the bridge swayed so much that the sensible beast stuck out all four feet, and stood still till it stopped swinging.

On this occasion we elected to try the rope bridge for the first time. It was not nearly so alarming as it |47 looked. The bridge is made of ropes of twisted birch twigs, each rope being about the thickness of a man's arm. Three of these make the footway, bound together here and there by withes; the hand-rails are similar ropes, the footway and hand-rails being fastened together by light one-inch ropes at every six feet or so. All three sets of ropes pass over one piece of timber set across uprights on each bank, and they are anchored as a rule to another baulk of timber buried in loose stone masonry. Advantage is taken of a high rock or bit of cliff for a take-off; the nearer both ends of the bridge are to being at the same level the better, but this is not essential, and one end may be twenty feet higher than the other. Even with the take-off at each end on a level, the bridge sags very much in the centre; if there is much variation in the level the pitch at one end is necessarily much steeper than at the other, and at either end there is a very decided slope. This is trying for a tall man, for the nearer to the anchorages the shallower the V made by the ropes, and in order to get hold of the side-ropes you must stoop forward very much, which is apt to be unpleasant when you necessarily look down and see, sixty feet below you, hard rocks. Once you get above the water all feeling of discomfort passes off, and in the hot weather it is |48 pleasant to stand leaning your back against the side-rope, swaying in the wind, and facing the cold air which rushes down above the centre of these ice-fed torrents. In order to prevent the side-ropes getting close together they are kept apart by sticks inserted at every few yards, over which you have to step. This is rather an acrobatic performance, as in the middle of the bridge the side ropes are two-and-a-half to three feet above the foot rope, but you soon get used to it. Every one crosses these bridges, old women, children, men carrying any loads, alive or dead. Some dogs negotiate them quite easily, but many get frightened and lie down, half way and have to be picked up. We had one pariah, who followed us from Kashmir, drowned, alas! three years afterwards in the Indus, who always tried to walk over the rope bridge, and invariably fell into the water when half way over. He did not try the Shaitan Nara: nothing that fell into that boiling torrent could come out alive.

From Ramghat the road runs for eight miles over an open sloping plain bordering the Indus to Bunji. This plain extends north for another ten miles, and is reported to have been richly cultivated, to have been partially ruined during the numerous wars at the beginning of the century, and to have had its |49 devastation completed by the great flood in 1841. This was caused by a gigantic landslip, probably following an earthquake. The whole hillside facing the Indus, just above the Lechur nullah, from a height of about four thousand feet above the river, was precipitated into the valley below, impinging on the opposite bank, and bringing down on that side a secondary hill-fall. The course of the river was completely arrested by a huge dam thousands of feet thick and some hundreds high; the water must have risen at the dam to fully a thousand feet above its present level. Whatever may have been the ordinary level then, the Bunji plain was converted into a lake, and the Gilgit river, which runs into the Indus six miles above Bunji, was dammed up for thirty miles to just below the present fort of Gilgit. The tradition is that the dam held for months, and that, when it began to cut, the river completed its work in one day, and swept down in a solid wall of water carrying all before it. All down the Indus valley to the plains the people were of course prepared for the rush, and though miles of cultivated land were ruined, one does not hear of much loss of life. But where the river begins to open out into the plains of India near Attock, a great disaster occurred. A portion of the Sikh army was encamped practically in the river-bed, |50 and the flood caught it and swept it away. In the picturesque native description it is said: "As an old woman with a wet cloth sweeps away an army of ants, so the river swept away the army of the Maharaja." All down the Indus valley ruined village lands covered with sand still attest the violence of the flood. You pass through a mile or more of the great dam, a mass of crumpled and distorted hillocks, on the road by the left bank of the Indus to Chilas; and the remains of a great pile of drift-wood left by the flood, which had for fifty years formed an inexhaustible supply of firewood for every traveller, shepherd, shikari, or raider who had passed that way, was still to be seen a year or two ago.

The Bunji plain now holds but a small fort, commanding the ferry six hundred feet below, and a patch of cultivation. It only wants water brought on to it to make it blossom like the rose. But the climate is not pleasant; the heat in summer all down the Indus valley is very great; 125° in tents is not uncommon in May. We found our camp very hot, as our tents were little double-fly tents, seven or eight feet square, just high enough for a tall man to stand up in with a few inches to spare. Our servants, orderlies, and guard were in single-fly sepoys' tents, and we were all |51 thankful for the shade of a few trees. We visited the fort, which stood on the edge of a great ravine leading into the Indus, surrounded on two sides up to the very walls by fruit-trees, under which some hundreds of Kashmiri irregular troops were now camped. All the arrangements for water-supply, magazines, and commissariat were of the vaguest.

At Astor we had begun to hear rumours of the heavy losses the Kashmir troops and coolies who had preceded us had suffered crossing the passes, pushed through as they had been in the early spring. Here we heard more details of losses by snow, and now the losses from cholera, dysentery, and other diseases incidental to bad food, over-work, and no sanitary or medical arrangements, began to be evident.

We crossed the river next day. It was running three hundred yards wide, a very mill race, with huge waves boiling over deep hidden rocks in the centre of its course. We crossed on a large raft, about eight feet by ten, made of a light framework of wood and bamboo, floated on half-a-dozen inflated bullock skins. It was a most exhilarating performance; once you had pushed out from the shore and began rowing, the raft was caught in the stream, and went dancing madly down, tossed in all directions by the waves, the men pulling for their lives so as to avoid being |52 swept past the landing-place and through the heavy rapids below. A few minutes of racing down-stream, and you pulled into quieter water on the opposite side, some hundreds of yards lower down than you started. All our kit, guard, etc., crossed in the boats, a much more dangerous performance, unless most carefully watched, for the Kashmir officials had never realised that the flat-bottomed boats, suitable to the navigation of the Woollar Lake, and of the quiet upper reaches of the Jhelum, were not fitted to the roaring stream of the Indus in flood. Consequently, year by year, they continued to build slab-sided flat-bottomed boats, and to man them with unfortunate impressed Kashmiri boatmen, accustomed to use a futile heart-shaped paddle instead of an oar; the natural result was that every year, as a rule, there was a disaster, and twenty to thirty men drowned The local officials did not even trouble to select the best place for a ferry; there were far better places a little up the stream. A Kashmir officer, while the arrangements for crossing were being made, explained to us the advantages of the rafts, and thoughtfully remarked: "The boat is very dangerous; we will not go in it ourselves, but send the coolies and guard." I crossed often afterwards by boat, but it was most unpleasant, and with a lot of men and horses in it, really unsafe |53 There were the usual casualties this year, a couple of boat-loads of men being lost Two years afterwards Robertson lost the whole of his kit, especially got together for his exploration of Kafiristan, a couple of horses and about twenty men going down at the same time, owing to the officer in charge having allowed the boat to be overloaded. Luckily for Robertson he was not there, having gone up-stream to look at a bridge site for me, but it was an expensive way of having the lesson rubbed in that you should never in wild countries permit other people, however well-meaning, to take charge of your baggage.

The road led up from the Indus through a bare plain to the Sai valley and passed through thousands of acres of once cultivated land, now almost entirely abandoned. We halted to breakfast and to pass the heat of the day at Damot, a village at the mouth of the Damot nullah, famous for its markhor ground, in an orchard which was a great natural arbour bound together by countless vines. Amongst these, making at a distance a lovely picture, little naked boys played and swung on loops of vine; close at hand they were too dirty to be even picturesque.

We passed on the road a group of Balti coolies, who threw themselves at my horse's feet in a body, and prayed for help. There was nothing I could do |54 for them at the moment, though the mere fact that I enquired into their grievances had, as I afterwards heard, a good effect, and got them dismissed to their homes, but Robertson stopped behind to see what a little doctoring could do. It was not much; the men, fifty-three in number, were the remains of a body of a hundred coolies who had left Baltistan six months before, impressed by the Kashmir authorities as transport for the army assembling at Gilgit; they were, to a man almost, suffering from diarrhoea and dysentery brought on by overwork and bad food, and several were dying, the worst cases being placed by the runnel of an irrigation channel, close enough to reach the water with their hands. This was all the help their companions could give them. Forty men of the original band were said to have died, the remainder were being slowly worked to death, and were then being taken to Bunji to bring up grain to Gilgit for the troops. One poor wretch had a hole in his back where his load had worn away the flesh. The whole thing was sickening; war is bad enough at any time, but mismanaged war is hell.

In the evening we moved further up the Sai stream to Chakarkot, another pretty little camp in the village orchards.

The next three marches to Gilgit were at that time |55 horrible, through a howling wilderness; for nearly twenty miles there was not a drop of water, except when the road dipped right down to the bank of the Gilgit river, and that was running thick and slab like gritty cocoa. Up and down over spurs of hills, into gaping ravines, now at the level of the river, now a thousand feet up, along cliffs glaring and blazing in the sun, the miserable path ran on. Going free and comfortable as we were, it was easy to realise what such a road meant to laden coolies or troops. Once we had some rain at night, and were treated on a small scale to one of the most curious phenomena to be met with in this weird country, namely, the mud flow, which forms the alluvial fan.

If you stand high up on a mountain side, in any part of the Hindu-Kush, and look up or down the valley, you will always see projecting into it, at varying intervals, usually making an angle of from ten to fifteen degrees with the river level, and invariably at an entirely different slope to that of the main hillsides, a series of fan-shaped spurs, poured out as it were from the mountains behind. These are the alluvial fans on which in almost all cases the first cultivation in a valley commences, and from which, if there is flat ground round their bases and enough water is available, the cultivation extends. The fans |56 are formed by streams draining the inner mountains which have cut their way through the hills forming the main valleys. They are composed of boulder clay, and show very often distinct traces of stratification. Rain rarely falls below an altitude of eight thousand feet in these parts, and the streams as a rule can cope with the drainage from the hills. But in the spring, when the heavy melt of snow commences, and when consequently the hills above that level are for days together clothed in mist and drenched with rain; or in summer when, after ten days of brilliant weather, a three days' storm rages and the fountains of heaven are opened on the higher hills, the streams cannot drain the hillsides sufficiently quickly. They become heavy with mud, loosened boulders crash into them and are swept down, the main ravine becomes more and more choked as the tributary streams pour in, and at last in a solid mass forty, fifty, sixty feet deep, it pours its stream of mud, out of the hills into the river valley, the stream at once expanding as it leaves the embrace of the enclosing cliffs. In this way every fan has been formed, the stream which made it cutting its way through its own fan to reach the river. The mud flow of which we saw the traces was a mere baby; it had only covered rocks ten feet high in the stream bed, and made a miniature fan where it |57 debouched, but its force was attested by the huge boulders it had moved. These mud flows come down with terrible rapidity and irresistible force, and with no further warning than a tremble of the ground like an earthquake and a grinding roar, followed immediately by the wall of mud and rock: man or beast caught in a ravine by them is lost. The peculiar formation so common in the Hindu-Kush by which a stream, with a catchment area "perhaps thirty to fifty miles round, cuts its way into the main river through a gorge fifty feet wide, with walls several hundred feet in height, is what makes these mud flows possible and so dangerous. No one who had not had his attention drawn to them would believe in their action. When making the road down to Chilas in 1893 I found a bridge being built over a ravine apparently in a perfectly safe situation about thirty feet above the bed. The engineer in charge would not believe that it could be unsafe till I showed him on the cliffs not fifty yards from the bridge traces of a mud flow, which I knew was only a year or so old, some thirty feet higher than his bridge site.

About twelve miles from Gilgit we passed lines of sungahs, stone breast-works, following the edge of the cliff above the river, and blocking the ravine heads leading into it, and asked their meaning. The |58 road at this point dropped into the river bed, and led for a few hundred yards along a flat sandy bank by the water's edge. We were told that the place was called "the fort of Bhoop Singh," from a Kashmir general of that name who, some forty years before, had marched up to the relief of Gilgit. Instead of pushing on to the high ground beyond, he had halted his men here, and had neglected to hold the heights. Immediately taking advantage of his folly, the insurgents who were beleaguering Gilgit came down during the night, seized both the paths leading up from the river bed, and built the sungahs we saw, while the Hunza-Nagar men came down and took up a position on the opposite bank. After some days of hopeless fighting, the force, which numbered twelve hundred, was wiped out, every single man killed or carried off into slavery.

One could see the tragedy; the wretched men under a plunging fire, with inaccessible cliffs above them, and a raging torrent in front of them, badly equipped, badly led, and with nothing but death or worse staring them in the face. It was a useful reminder to all soldiers passing by. I never rode through the place without feeling the horror of the long past days of agony, and without having the difficulties and dangers of campaigning in such a country |59 forcibly brought in on me. It would have saved us many a life before some years were over had all ranks, British and native, taken the lesson to heart. But it was not to be: each generation must apparently make the same mistakes, men will be reckless, and some apparently can only buy experience with the wasted blood of their men, and gain common-sense for themselves when it comes to them hand-in-hand with death.

The approach to Gilgit is rather fine. The road runs up the flank of a huge alluvial fan several hundred feet in depth, where it bursts out of the hillside, and which stretches a mile into the valley. From the east as you approached you saw then no trace of cultivation, only line after line of ruined terraced fields bare and brown. High up on the main hillside, visible for miles, stands a Buddhist tower, the land-mark which must for centuries have welcomed the traveller to Gilgit. The extraordinary dryness of the climate, with its average rainfall of under a couple of inches a year, has kept it, ancient as it is, in a state of almost perfect preservation.

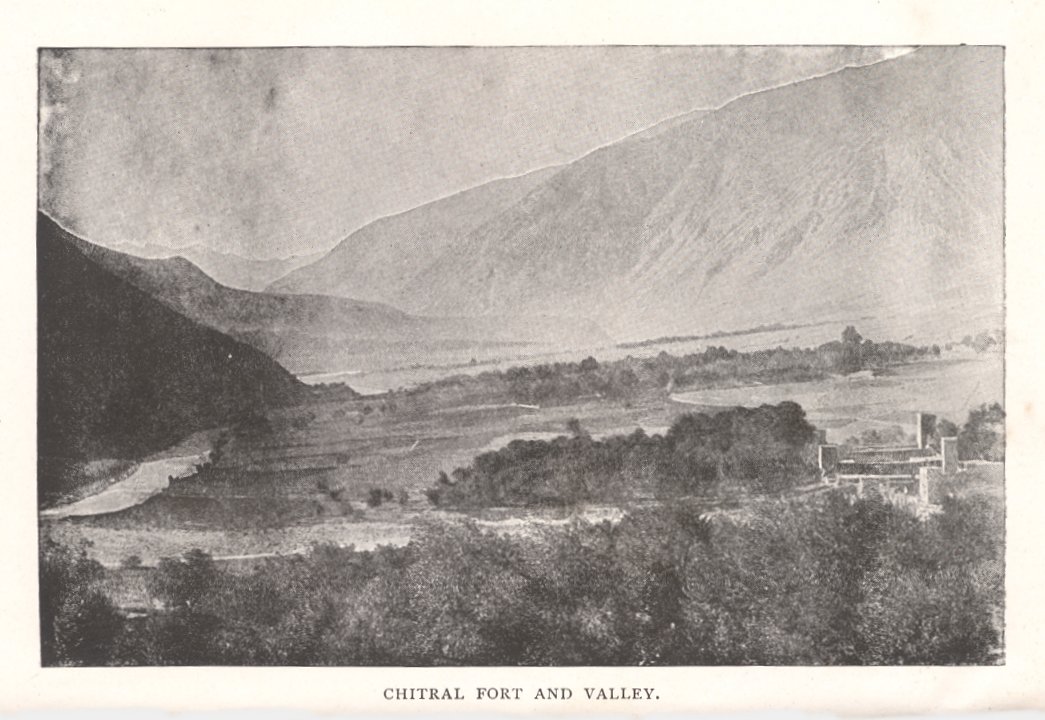

From the. highest point where the road crosses the fan there is a splendid view of the triple peaks of Rakapushi, the great mountain above Nagar to the north, and the Gilgit oasis bursts into view. This is |60 a mass of cultivation five or six miles long by a mile wide at the widest, studded with villages and covered with fruit-trees, the whole irrigated and depending for its water on one stream which enters the valley at the western end.

I was met on the road at intervals by all the important men in Gilgit; the lower the status of the official the further he came out, according to Eastern custom, to receive me. The rajas of Punyal, the country tributary to Kashmir, which is the continuation of the valley of the Gilgit river towards Chitral, refugee princes from Yasin, driven out by the Mehtar of Chitral, local wazirs and Kashmir officials met me one after the other, the culminating point being my reception by the Governor of Gilgit and the officers of the Committee directing the operations on the frontier. It was a motley crowd and picturesque, but I was glad when, after passing the fort, we were conducted to the house built in Major Biddulph's day, and left there in peace.

The next few days were spent in making acquaintance with the Governor and the members of the Committee, which consisted of the General commanding at Gilgit, the General commanding the regular reinforcements, the Sunadés or officer commanding the irregular troops, and of a couple of high |61 civil officials, the most important of all being Mehta Sher Singh, an old gentleman of high family and position in Kashmir. The ablest among these gentlemen was, perhaps, the Governor, who had held his post for eight years, was heartily sick of it, and was most anxious to settle matters with Hunza and Nagar somehow, and to be permitted to return to Kashmir. He was an adept at intrigue, the threads of all the frontier affairs were in his hand, and the puppets on both sides of the border generally danced at his bidding.

My position was difficult; I had distinct orders not to give advice, but I could see very well that, if the negotiations going on failed, the Committee would come to me for it, and that whatever decision they came to, the onus would be thrown on me. Every endeavour was of course made to throw dust in my eyes, and to prevent my getting information as to what had really happened, why the tribes had broken out, what was going on at the moment, and as to the condition of the troops. I was told, however, and I knew the information was true, that between Astor and Nomal, the fort eighteen miles north of Gilgit, then the last Kashmir outpost towards Hunza and Nagar, the Durbar had a force of eight thousand men. I knew, what I was not |62 intended to know, that the men were half starved, fed on the worst form of grain, the food-grain which ought to have been in the granaries having been fraudulently made away with, and that there was only a month's food for the troops on the Gilgit side of the Indus, and no carriage to bring on any more. The Durbar had poured hundreds of tons of grain into Astor, which was easy enough to do, but had left it to the local authorities to forward this to Gilgit, a task, with their then resources, impossible of accomplishment.

I have before described the want of system which existed, so I was not surprised at what I saw en route and at Gilgit. Here I found the Kashmir regiments scattered all about the valley in orchards, a sensible enough measure, as they had suffered considerably from cholera, but without a semblance of military precautions being taken. The senior officers never visited their men, not once were the troops under arms during my stay, and I do not think they had ever been properly fallen in since they had left Kashmir. Some days after my arrival at Gilgit nine hundred men were despatched unarmed, without an escort even, and without one single superior officer, four marches back, to fetch up for themselves a month's grain. The day before I arrived the |63 troops were issued a day's supply of good flour to disarm enquiry on my part, but, as a rule, their food was vile, and the men received nothing but two pounds of unground grain, absolutely no extras, not even salt. What could be done with troops so treated? The men were well enough, and, poor wretches, looked eagerly to my coming to relieve them of their misery. Some of the officers were keen, but peculation and corruption were rampant; the honest men, if they existed, had no chance, and the condition of the force was deplorable.

If from the military point of view things were bad, from the civil they were no better. The Durbar was robbed by every official from the highest to the lowest; granaries that should have been full of good grain were empty, or full of rubbish substituted for a consideration, bribery and corruption ruled the land, disloyalty and treachery were in its high places. The man to send warning to the Hunza-Nagar forces, when after the capture of Chaprot they had advanced south and were besieging Nomal, the last Kashmir fort between them and Gilgit, of the advance of the Kashmir troops to its relief, was the Governor of Gilgit's right-hand man, Wazir Ghulam Haidar. Every one knew this, yet he was still employed and passed backwards and forwards between both |64 sides, apparently the trusted servant of the Governor. A more villainous-looking scoundrel I never saw. He came one day, bringing the sons of the Raja of Nagar, who had come as ambassadors from their father, to see me. One of them had some years before been made Rá or Chief of Gilgit by the Durbar, the old line of chiefs having died out, and he having married the last surviving girl belonging to it. He had distinguished himself by bolting from Gilgit and leading the attack of the Nagar forces on Chaprot some months before. I thought this rather ungrateful at the time, till I found that, with the Governor's connivance, Wazir Ghulam Haidar had previously seized his best house and lands. It was double-dealing of this kind which had brought on the troubles for the Durbar, a mixture of weakness and bullying, fear and swagger, which had half-frightened and half-exasperated the tribesmen into attack. There was also a Helen in the case.

A fortnight at Gilgit put me in full possession of the leading facts bearing on the existing difficulties, which may be summarised as follows:----Hunza was extremely difficult of attack, and practically could have but little pressure brought to bear on it, having exits to the north on to the Pamirs. It could get |65 all its luxuries from Kashgar and Yarkand, and had some connection with China; an Amban being at the time I was in Gil'git, or shortly before, in Hunza, to enquire as to the cause of the trouble. He was plundered and practically sent naked away, but that is another story. Nagar being a cul-de-sac, and depending for its salt and other luxuries on Gilgit, could be squeezed, and was, moreover, supposed to be easier of access. The Durbar, while jealous of its military reputation, and ostensibly making great preparations for war, really wished to avoid fighting, and was anxious to arrive at peace by any means in its power. The Committee at Gilgit fully recognised the difficulties of supply and carriage, and were also most anxious to come to some modus vivendi. The Hunza-Nagar people were sick of the game, and wanted to make peace, so that the men might look after the crops instead of spending the best part of their time sitting like vultures on the tops of cliffs on the look-out for the Kashmir army of invasion. With things in this condition, and nothing much more to be learnt, there was no use in my staying longer, and I welcomed the invitation I now received from the Mehtar of Chitral, and prepared to start for that country.

And here, perhaps, will be a fitting place to |66 point out more clearly the importance of Gilgit It is a poor valley, separated from India by snow passes, situated on the far side of the Indus at the extreme verge of Kashmir territory. Why, it has been asked should it be worth our while to interfere there whatever happened ? The answer is, of course, Russia. She had advanced practically to the Hindu-Kush; it was necessary to see that she did not cross it. No man in his senses ever believed that a Russian army would cross the Pamirs and attack India by the passes of Hunza and Chitral, but we could not overlook the fact that in 1885, when war hung in the balance, some thousands of her troops were moved down towards the Pamirs. What was this for?----hardly for change of air or to shoot big game, as the British public were asked to believe later, when similar moves were made. The object was to get a footing on the south side of the Hindu-Kush, and to paralyse numbers of our troops who would have to be kept in observation of possible Russian lines of advance. Further, I have no hesitation in saying, and I know every inch of the country, and every important man in it, that at the time of which I am now writing, had war broken out between us and Russia, there was absolutely nothing to prevent a Russian officer, with |67 a thousand Cossacks, from reaching Astor in ten days after crossing the passes of the Hindu-Kush, and from watering his horses in the Woollar Lake four days later. The Kashmir troops usually kept on the frontier would have gone like chaff before the wind, and there would have been no local opposition; far from it, an invader promising the loot of Kashmir would have been welcomed. We should have been treated in India to a bolt from the blue.

That a thousand Cossacks could not hold Kashmir is very true, but think what the effect in India would have been when the Maharaja and his Court, the Resident, and any Europeans in the country, came tumbling out of Kashmir, flying from a Russian force, the strength of which no one could tell. There would have been no British troops within two hundred miles of Kashmir, all eyes would have been turned to the Peshawar and Bolan fronts where our troops would have been massing, and the word would suddenly have gone forth----"The Russians have turned our flank, they are in Kashmir, and will be in the Punjab and on our line of communications in a week." The consideration that though the main fact might be correct the deduction from it was unsound, would have carried but little weight. |68 Public opinion, both in India and England, could not fail to be seriously stirred by the invasion of Kashmir, the wildest rumours would have been credited, the most dismal prophecies believed. The alarmist within the country is a worse enemy than the foe at the gates. For the moment the effect would have been stunning, and though in the end we should have recovered from the blow, it would have been a terribly effective move with which to open a campaign. Let people consider for a moment what a born leader like Skobelef would have made of a chance like this, and they will, I think, agree, that expensive as the Gilgit game may have been, it was worth the candle. |69

FIRST VISIT TO CHITRAL

AFZUL-UL-MULK, second son of the Mehtar or King of Chitral, who had passed the winter in a visit to India, and had been in Kashmir as I passed through, now arrived in Gilgit, and came to see me. He was generally known in Chitral as the Tsik Mehtar, or little Mehtar, his elder brother Nizam-ul-Mulk, in consideration of being heir-apparent, having the title of Sirdar. He was a good-looking young man with beautiful eyes and well-shaped face, the mouth being the bad part, the lower lip of which was heavy. It was the family feature, borne by every Katúr, as the clan of the ruling family was called. Colonel Lockhart had taken a great fancy to Afzul-ul-Mulk, and he had certainly a taking personality. Bright, cheery, of an enquiring turn of mind, talking Persian fluently, as does every gentleman in the Hindu-Kush, interested in everything he had seen in India, realising what the British power meant better |70 than his father, who had never left Chitral, and extravagantly loyal, open-handed, courteous to all, young, handsome, hospitable, a good shot, and, for a Chitrali, a fine rider, it would have been curious if he had failed to be popular. But there was a different side to his character, as I very soon learnt. At heart he was a pure savage, a mixture of the monkey and the tiger. Loyal from calculation, and from hopes of being recognised by Government as the heir-apparent, he was, under his cloak of open bonhomie, generosity, and transparent honesty, the most persistent plotter, and the most treacherous and ruthless foe. At his father's death, he very naturally seized the throne, and his elder brother fled the country, defeated by superior powers of intrigue. But with all his cunning Afzul-ul-Mulk was a fool. He tried to strike terror by cutting down the leading men; he cut down too many or too few. The cold-blooded and treacherous murder of three brothers would have passed with little comment, the death of leading adherents of his brother was natural, but the announcement that a list of head men existed, who were to be killed, and the uncertainty as to whose turn was to come next, were too much. A carefully prepared plot, hatched in Afghanistan, overthrew him; his trusted adherents betrayed him, his most confidential servant opened |71 the gates of his fort and let in the enemy, and he fell as he had risen, by treachery and murder.

However, at the moment, everything was rosy. No shadows of coming events chilled us, and I gladly arranged to accept the Mehtar's invitation to visit his country, so courteously delivered by Afzul. It was decided that he should move on ahead of me, as he took up a great deal of carriage, and that he should await me at Mastuj, the headquarters of the district he governed. I wanted a few days to arrange about my carriage, and to take farewell of my Kashmiri friends, to each one of whom I had to make a present of more or less value on the part of Government.

We were not sorry to start; the valley was horribly hot and unhealthy, the rice cultivation in full swing, the fields a sea of putrid water, cholera was more or less all round us, and. we had both been rather out of sorts. The measures taken to stop the cholera were curious. No attention was paid to such trifles as water-supply or sanitation, but morning and evening the Brahmins used to march round the camps of the troops, blowing conch-shells and invoking their gods, a plan which, however effective against the walls of Jericho, left something to be desired during a cholera epidemic. |72

We found the country we marched through to Gakuch, the last fort in Punyal, and for many marches beyond, wilder than anything we had yet seen. For the most part the road runs through a narrow valley just wide enough to give room for a roaring torrent sixty to eighty yards across, with an average fall of forty feet to the mile, the valley here and there opening out and showing alluvial fans and patches of cultivation. The two most marked features of the road for a hundred miles from Gilgit, and practically throughout the Hindu-Kush, are shingle slopes and the "parris." Thousands of feet above you are the mountain tops, shattered by frost and sun into the most fantastic outlines, from whose rugged summits fall masses of rock. Below any precipice you consequently see the shingle slope in existence; these slopes sometimes running up thousands of feet at a steep unbroken angle, almost universally of thirty degrees. The sizes of the stones forming the slope vary with the character of the rock and the length of the fall. You may pass through the foot of a slope by a path running over and amongst a heap of gigantic fragments weighing many tons each, or you may ride across a slope of fine slatey shingle which gives at every step, but wherever you cross a slope you |73 generally find all the stones at that point very much the same size. Whenever there is heavy rain, or snow begins to melt in the spring, rock avalanches come down, and I have lain at nights for hours listening to the thundering roar of great fragments plunging down from thousands of feet above one's camp. In the day-time you have to keep a sharp look-out when marching. There are many places well-known as extremely dangerous, in crossing which it is prudent not to loiter. I have never seen a man killed, but I have seen a man's leg broken a few yards in front of me by a falling stone, and have witnessed very narrow escapes. There was one particularly nasty stone shoot at Shaitan Nara, where stones fell all day long, the smaller whizzing by like a bullet, and the larger cannonading down in flying leaps, the last of which frequently carried them nearly across the Astor River. Starting stone avalanches on to an enemy below is a well understood and thoroughly appreciated form of warfare in these parts, and a very effectual means of offence it is.